THE SEAGRAM BUILDING

The Manhattan skyline is in many ways the ultimate representation of the people, culture, and history of New York City. You see peoples’ entire lives. Where they live, work, dine, play. It is an entirely contemporary view, yet it is created by layers of history and change. Wall street defined by art deco, SoHo the first cast iron structures, Midtown Post-Modernism, Uptown the beaux-artes. This ever changing mixture of aesthetic is symbiotic with the city and its people. The center of change, culture, style, and innovation. The landmarked buildings and districts of New York protect the fabric of this city and allow diversity and culture to expand and survive at the foundational level– through our infrastructure. A major turning point in the history of this city and the world, was the shift towards Modernism. Shifting philosophies and the rejection of traditional values in the wake of the World Wars led people to search for new ways of living and creating. Situated at 375 Park Avenue, the Seagram building stands as one of the first buildings of its kind in the United States, embodying this change in style and culture which is as relevant today as it was at its time of construction.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe grew as an influential figure in Modern architecture in his pursuit of European avant-garde design. He was known for a flair for the dramatic, while still creating subdued, streamlined works. At the 1929 International Exhibition, his creation of the Barcelona Pavilion demonstrates these themes at their best. With hallmark traits of the international style, he designed a throne room in its most neoteric form. Precise geometry and celebration of material in its purest form define this early work. Use of glass and steel imbue the structure with a sense of functionality, while travertine, onyx, and marble remind the audience of its basis of nobility.

Exterior and Interior of The Barcelona Pavilion

In addition to recognition for his personal architectural work, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe also served as the last director of the Bauhaus school in Germany. The Bauhaus school was a powerhouse in the pursuit of revolutionary art and design during the early Modernist movement in Europe. The school’s value of fine art, craft, and architecture radically reshaped the fabric of art and design in Europe, and eventually globally. Increasing political turbulence and violence in Germany during the late 1920s and early 1930s led to the closure of the school in 1933. Modernism, deemed “degenerate art” by Hitler, was condemned by the Nazi regime, who persecuted and exiled any artists associated with the movement. In 1939, Mies van der Rohe fled Germany and immigrated into the United States, settling in Chicago.

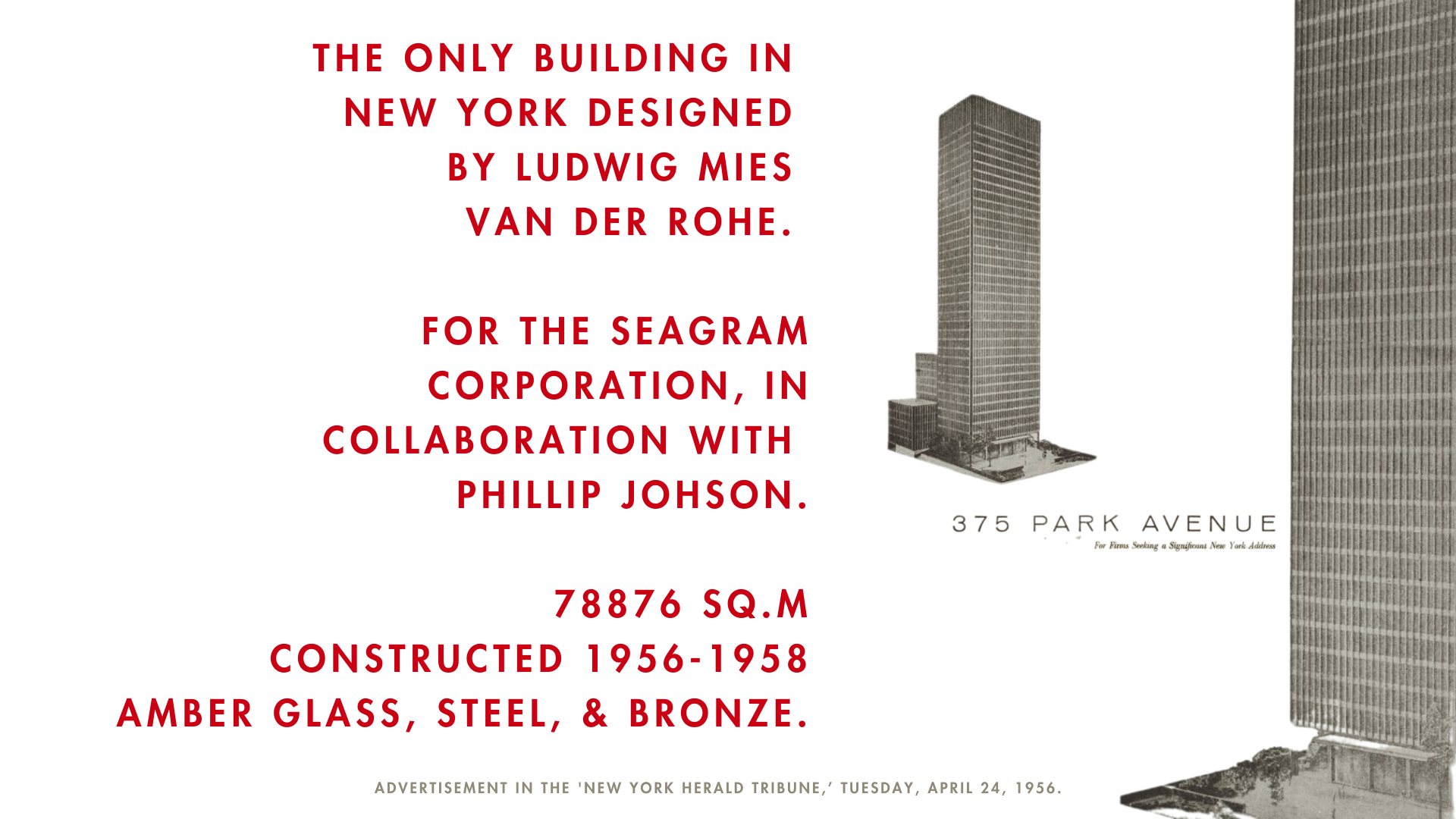

In the early 1950s, Samuel Bronfman, the president of Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, the beverage company, began searching for an architect and a site for their Manhattan offices. After considering the more traditional and American mainstream styles of the Metropolitan Club, Montana Apartments, and Racquet and Tennis Club, Bronfman ultimately pivoted to the sleeker, more forward-thinking International Style. The selection of Mies van der Rohe as architect for the project came from Bronfman’s desire for luxury and legitimacy, values deeply intertwined with Mies’s own design philosophy and body of work. This decision was sought through by his daughter, Phyllis Lambert, whose time spent living in Paris and working as an artist made her the chief proponent of the avant-garde nature of Mies and European Modernism.

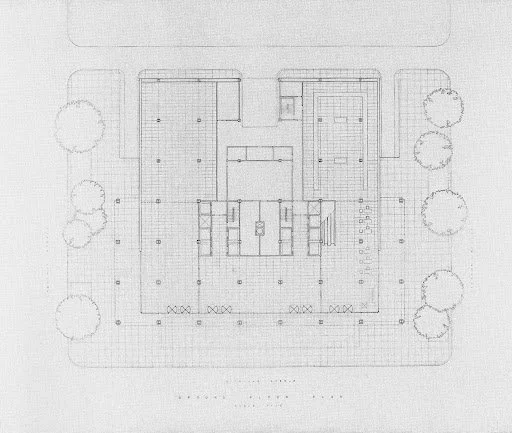

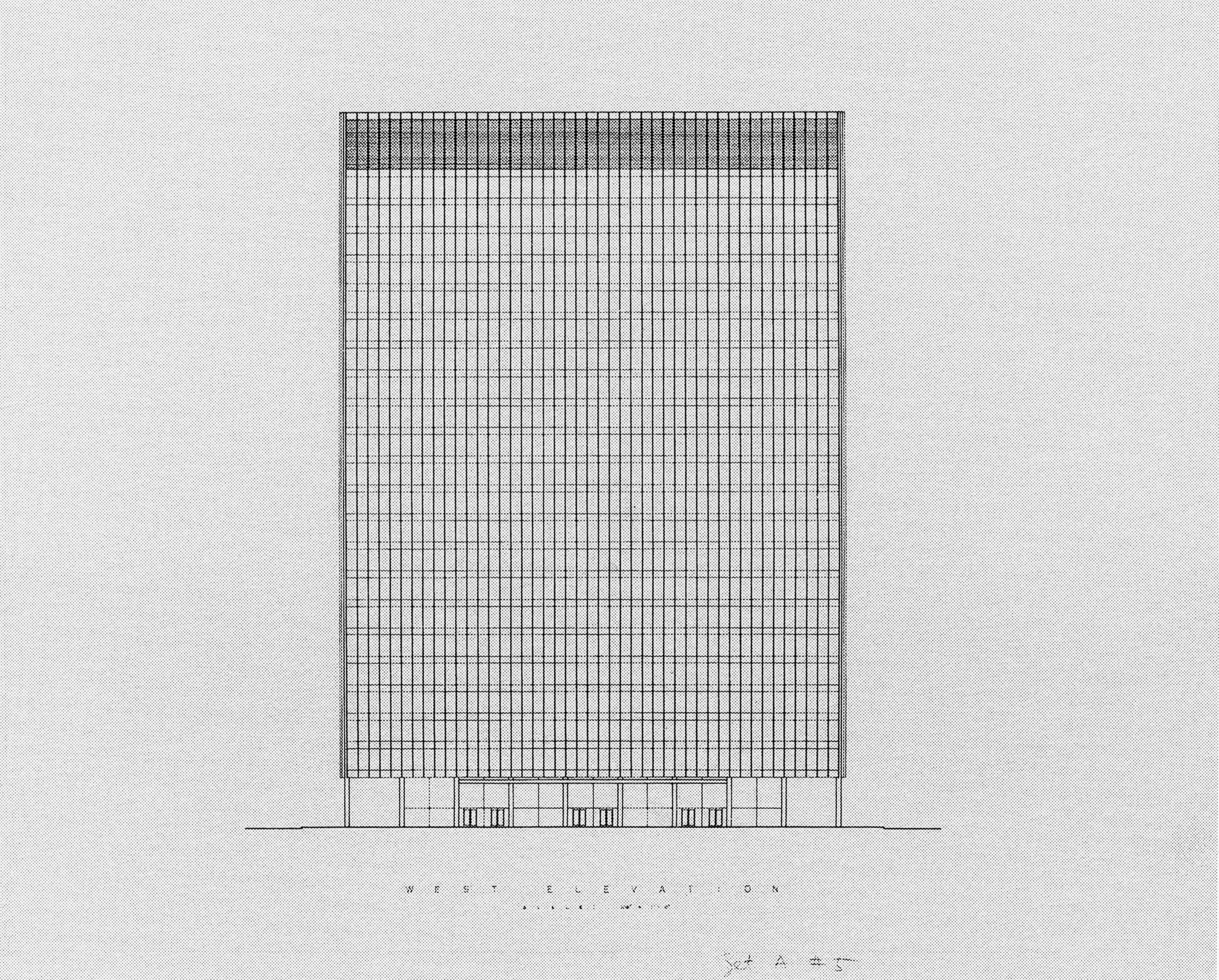

Floor Plan and Elevation of the Seagram Building,

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe

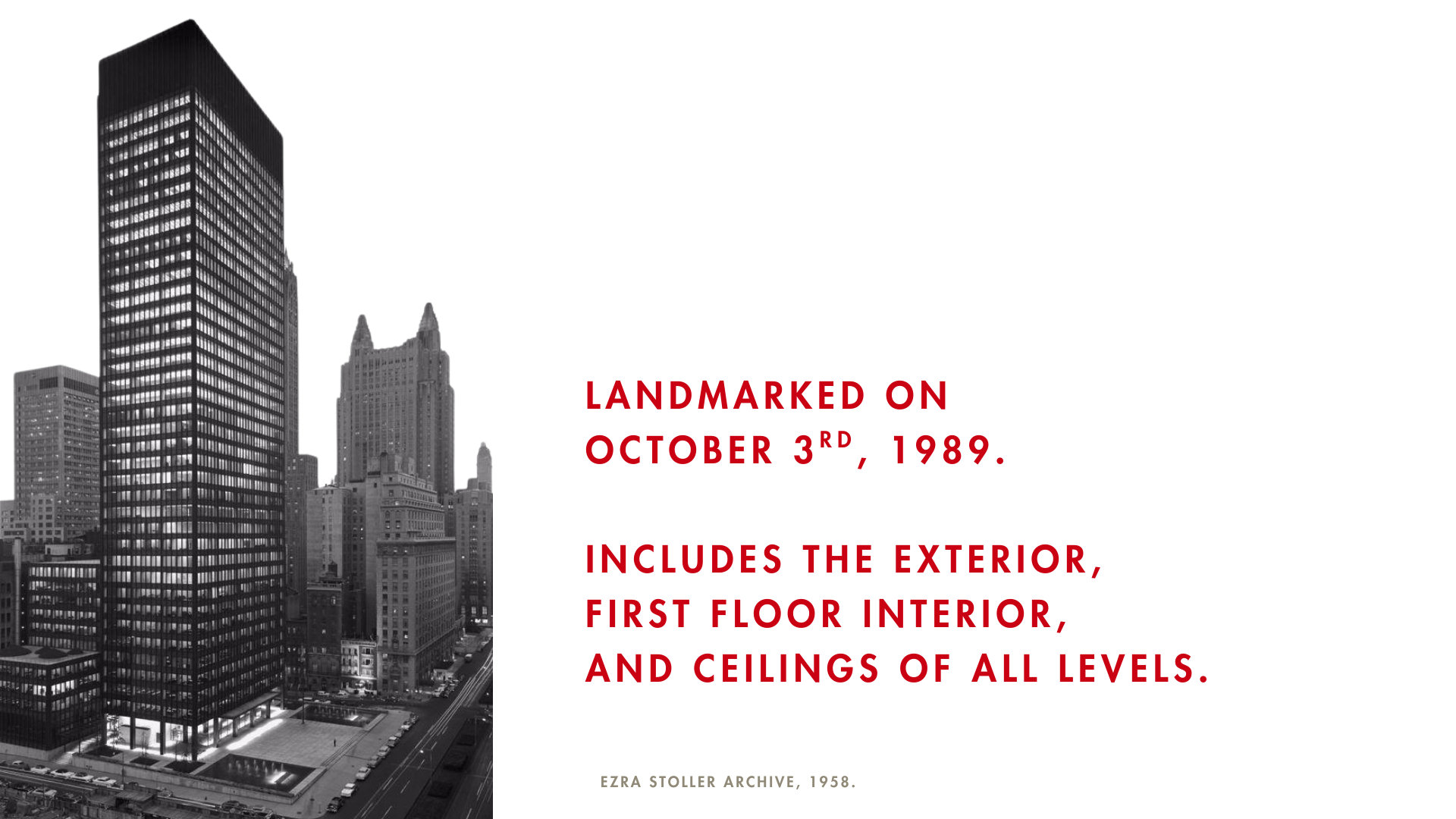

The Seagram company saw the value of this building, they were proud of this accomplishment and wanted to extend their legacy through the protection of this building. During and after construction, detailed and thorough maintenance protocols were instituted and enforced to keep the building’s interior and exterior intact and beautiful. When the Seagram building was landmarked, on October 3rd 1989, the Landmarks Preservation Commission remarked on how impressive the existing preservation efforts had been, and how effectively protected the building had been until this point. Due to the cultural importance of Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, the historical implications of the introduction of the international style to the New York City cityscape, and the continued inspiration to new generations of designers, the Seagram building was deemed a landmark building. At the point of its construction, in the 1950s, the Seagram building demonstrated the changing values and aesthetic interests of not only New Yorkers, but also of the cultural zeitgeist. People were looking towards the future, embracing Modernism and technology in a way that really hadn’t happened since the industrial revolution. This sleek, singular building was a visual characterization of the desires and needs of people during that time.

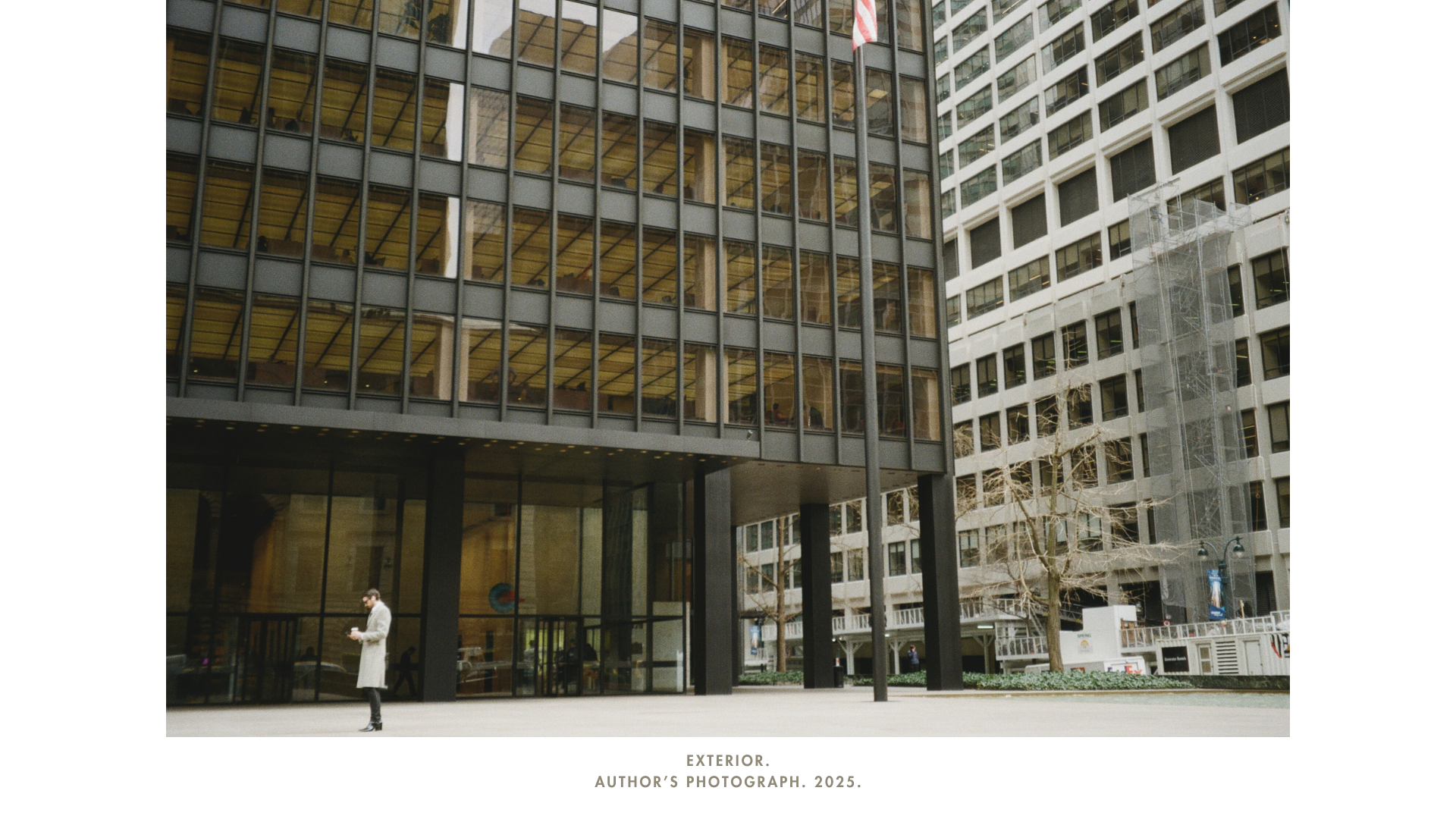

Design of the Seagram building, headed by Mies, supported by Phillip Johnson, and overseen by Phyllis Lambert, was radical in its form and sensual in its materiality. Simplicity of structure is one of the elements of this design that makes the Seagram Building so visually stunning and surprising. The exterior, set back on a plaza, stands as a solitary vision against the background of Park Avenue. Broad expanses of glass windows, geometric gridding of bronze, and the subtle hinting of interior lighting define the facade of the building. The main structure of the building, raised on hallmark piloti, frames the only semi-public spaces in the building, the first floor reception and restaurant.

Reception and washroom of the Seagram Building. Ezra Stoller, 1958.

Entrance into this tower is extended only to the fortunate few, even access to the first floor is relegated to the elite employees and privileged diners. The sculptural elements present at the exterior and the plaza extend as the visitor enters the building. Sleek spans of green travertine define the perimeter of the space, conveying clarity to the viewer and telling the story of the Seagram brand. The other element to the first floor, the restaurant, further enhances the feeling of luxury and richness associated with the Seagram building. From the sleek uniformity of the halls, the restaurant opens up into a bustling, high ceilinged atmosphere, a perfect representation of the spirits brand. Wood panelling lines the internal walls while curtain windows are treated with swags of fine-gauge aluminum chains. Furniture by Van der Rohe, Saaranen, and Knoll are spaced with full sized trees, representing the changing of the seasons. But the main event of the space is the lighting sculpture by Richard Lippold, a sparkling bronze work which spans the ceiling above the bar. Like a crown atop the head of a royal, the sculpture rests at the peak of the space, drawing you in and making you feel the grandeur of the room.

The original Four Seasons restaurant. Ezra Stoller, 1958.

In 2001, the Seagram corporation ceased operations and sold the building to RFR Holding LLC. The space formerly home to The Four Seasons restaurant is now The Grill. While the furnishings on the interior of the restaurant have been changed from their original design, the architectural structure and art installation remain, reminding us of Johnson’s amazing accomplishment, and giving it new life in the context of the day. Outside of the exterior and first floor interior of the building, only the ceilings of each additional level are landmarked. Arguably, the inclusion of these ceilings is an addendum to the landmarking of the exterior. The chief effect of the preservation of these ceilings is felt by those who gaze at the building from below. Whereas neighboring buildings have variation of ceiling and lighting design, the Seagram appears consistent all the way through. The intention of uniformity extends to the peeks of light you see through the amber glass, and this addition to the landmarking ensures this intention holds as time goes on.

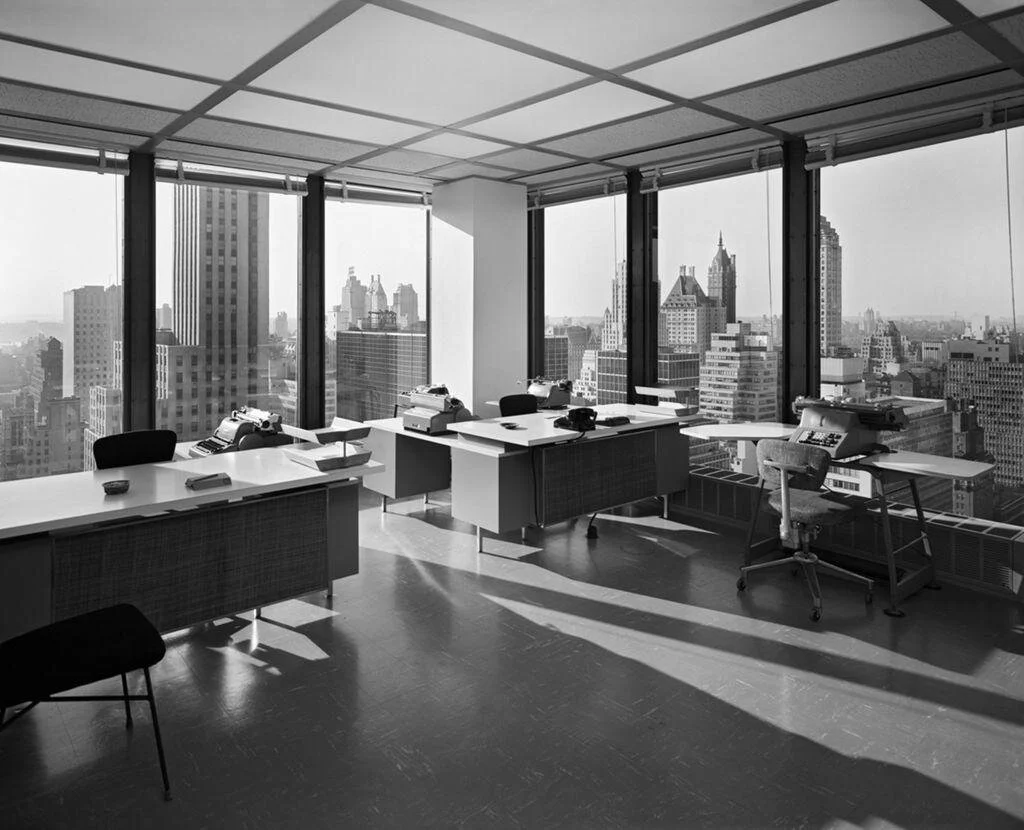

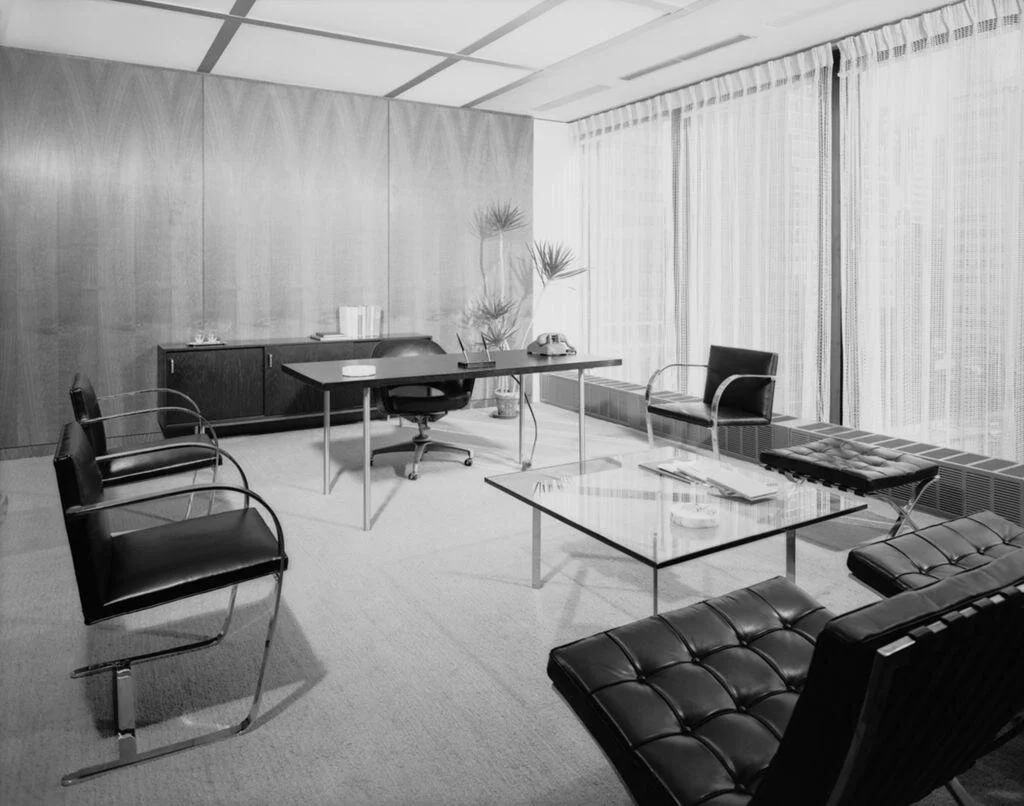

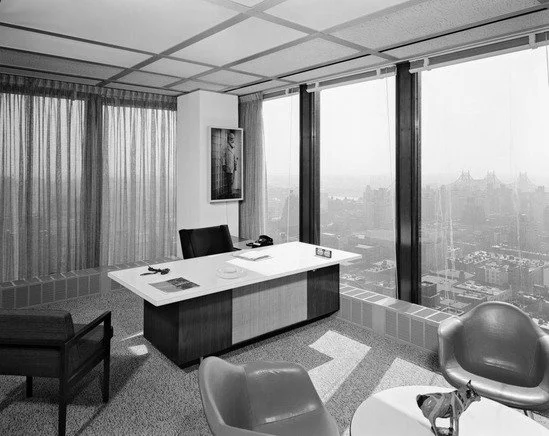

Although the offices, lobbies, and conference rooms of the original design are not preserved, we still have images of these spaces to reference and enjoy. The original furnishings of the space contribute to the feeling of a total work of art. Integration of furniture designed by the architect, as well as materials selections enhance the sleek, luxurious feeling of the space. From these images you can also see the internal impact of the ceiling plan and integrated lighting design. While providing uniformity, these ceilings also cast an ambient glow in the space, making lighting uniform and beautiful while supplying appropriate light for workspaces.

Private offices, landmarked ceilings visible. Ezra Stoller, 1958.

The Seagram building is not only visually stunning, and an immense achievement in aesthetic, it is also an embodiment of the cultural changes that were taking place at the time. The push for newness and change and a shifting towards the avant-garde and unexpected keep the building as relevant today as it was then. From the time of its construction to today, the Seagram building and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe have inspired generations of designers and artists. The preservation of this building reminds us of the legacy of these designers, and gives future residents and visitors of New York City the opportunity to become inspired.

Author’s photographs, 35mm film, 2025.

Sources:

House of Seagram. , (Patron), and Lustig, Alvin, 1915-1955. 375 Park Avenue. 1956 Apr. 24. Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.), JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.14633462. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, Kahn & Jacobs. Seagram Building. 1958. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.11960808. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, Kahn & Jacobs. Seagram Building. 1958. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.11971543. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson, Kahn & Jacobs. Seagram Building. 1958. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.11971724. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

Mies Van der Rohe, Ludwig. Seagram Building. 1958. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.16519529. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

Mies Van der Rohe, Ludwig. Seagram Building. 06/26/1959. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.16514965. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.

Mies Van der Rohe, Ludwig. Seagram Building. 06/26/1959. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.16515330. Accessed 5 Nov. 2025.

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. “Seagram Building.” 1989.

The Pavilion. Fundació Mies van der Rohe. (2025a, September 24). https://miesbcn.com/the-pavilion/

Philip Johnson. Four Seasons Restaurant. 1958. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.11934966. Accessed 19 Oct. 2025.