MORE A POEM THAN A HOUSE

The work of Philip Webb, best exemplified in his design of the “Red House,” a collaboration with William Morris, blended the arts with philosophy, striving to create a utopian ideal of a house. Every detail of the house was designed to work together towards this goal. The geometric forms of the exterior, the materials used, the window placement and types, and the interior furnishings all form a dance together, embodying the “total work of art.” The idea of the ‘gesamtkunstwerk” is that all elements of a design are created to unite an overarching work of art in which the designer has complete control over every element. While this can often lead to practices of the ego, in the case of the “Red House,” it is a practice of community. Philip Webb, William Morris, Jane Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddal and Edward Burne-Jones all contributed to elements of the house’s design and decoration (National Trust). The practice of working as a team to create the “Red House” contributed to the formation of the future manufacturing collective, Morris and Company, and led to the style known today as the Arts and Crafts Movement.

When William and Jane Morris commissioned their home from friend and architect Philip Webb, they wanted it to be a departure from the mainstream culture of design which they saw to be separating from the soul of creation and craft. In 1859, architects and designers were focused on integrating new technologies and working with industrialization, beginning to homogenize as the world became more interconnected. Morris and Webb wanted to turn back towards the vernacular architecture of the home in Bexleyheath, to feel that the home, the garden, and the land were all intertwined. The design of “Red House” was about connection. They wanted the house to feel like it had grown there, and they wanted to be able to feel the hands of those who had made it.

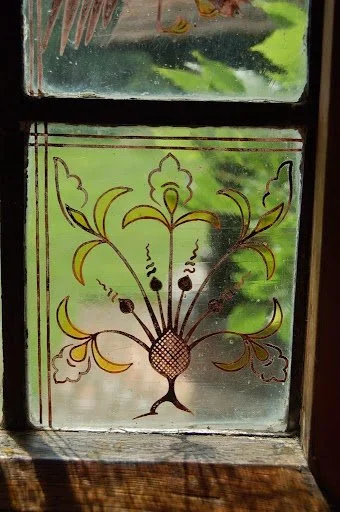

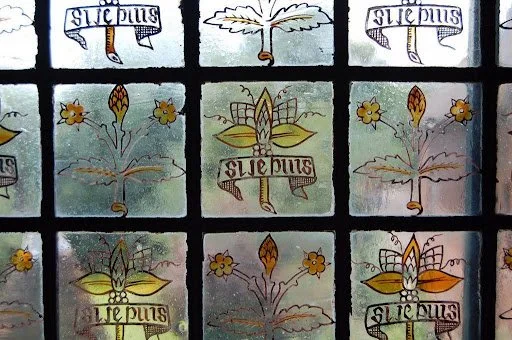

“Red House” was the harbinger of the movement which it defined: the Arts and Crafts movement, which gained prominence in England in the 1860 through the 1910s. The movement was born as a reformist ideal, merging socialism with romanticism. The idea was to create a home which referenced the forms of traditional homes in London, and used materials like brick which were associated with more “common” structures. Geometric motifs and decorative details echoed those that were popular in Medieval times, which was a reflection of the Pre-Raphaelite’s influence on the design. Even the smallest details, like the stained glass panels and painted furniture, reflected the core ideals of artistic expression, and revealed the hand of the maker.

When selecting the site for the home, Webb and Morris decided on this patch of land in Bexleyheath in part because of its convenience to London, but primarily because of a more romantic history. This plot of land had previously been a part of the Chaucerian route of the Canterbury pilgrims (Hollamby). Harmony with the land was fundamental to the conception of the “Red House,” planned to conserve existing flora, and flourish as its own contribution to the land. Looking onto the “Red House” from its grounds, it is clear that the home and garden were designed as one piece, each part supporting the other. Morris’s knowledge of gardening filled the grounds with beautiful flowers and plants, carving out spaces for leisure and sport, all in consonance with the home itself.

While Morris leaned romantic in his persuasion, Webb provided a more grounded and pragmatic approach to the design. The simple and geometric design of the house, laid out in an L shape, extruded into two levels, and accented with triangular gables, was produced based on need and function. Placement of windows further enhances this “form follows function” ideal, a concept that would grow to encapsulate the later Modernist movements. A highly individualized spatial plan, accented by specificity of fenestration and aperture, continues to be emphasized at all levels of the design.

Architectural Details of Red House. 1859.

As construction of the home went on, it became clear that such a singular house called for distinctive furnishings. The collective came together to create patterns for wallcoverings, embroider fabrics for upholstery and drapery, construct custom furniture (builtin and standalone), and paint murals and patterns on tiles, glass, and furniture. Every corner of the house was designed with intention and made to be beautiful. The interior forms are defined by the exterior volumes, left simple in their finishes, and filled with intricately detailed furnishings.

Stained glass work for Red House. 1859.

One of the most charming features of the exterior is the “well-house,” which stands in the garden at the inside of the “L.” The roof resembles a witches hat or a garden gnome, standing as a tall cone supported by a sturdy oak frame. The wood was to be “slightly wrot, and if not too rough, to be left with the saw marks” (Hollamby). This structure is a distillation of the idea of the home’s form. Based on simple geometry, resembling British vernacular architecture, grounded by choice of material, and displaying the hand of its maker.

When creating the light fixture, I wanted to focus on the idea of a central, geometric form supported by hand-crafted details. To me, the well form is so iconic to Philip Webb’s design and to the “Red House.” I used the organic, conical shape as the main form of my shade, and then developed a luminous base inspired by the handmade leaded glass featured in the windows of the house. I used wire to create the frame of the shade, bending it to reflect the shape of the well. I then used the technique of paper mache to create the shade from brown paper napkins. Referencing the “Red House” leaded glass windows, I hand painted four translucent paper panels, which I then framed with reused brown paper bags, and fixed to the main frame. I wanted it to feel handmade and organic, relying on structure of form while also celebrating decoration.

I really admire Philip Webb, not only for his aesthetic eye, but also in his philosophy and values. I think that focusing on community and craftsmanship in design is just as important today as it was during the time of the Arts and Crafts movement. The trajectory of design, leaning further into technology and away from individual creation, is taking away a lot of the creativity and life that has previously existed in design and architecture. I hope that a new movement focused on bringing back art and craft into the mainstream begins to take hold today.

Lantern, by author, 2025.

Sources:

“Arts and Crafts (Architecture).” Architecture-History.org, 2025, https://architecture-history.org/schools/ARTS%20AND%20CRAFTS.html. Accessed 9 Nov. 2025.

Burman, Peter. “‘A Stern Thinker and Most Able Constructor’: Philip Webb, Architect.” Architectural History, vol. 42, 1999, pp. 1-23. Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, Nicholas. “Red House: Some Architectural Histories.” Architectural History, vol. 49, 2006, pp. 207–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40033823. Accessed 11 Nov. 2025.

Hollamby, Edward. Red House: Philip Webb. Phaidon, 1991.

Lahikainan, Amanda. “Red House: Spatial Enclave of the Later Pre-Raphelites.” The Victorian Web, victorianweb.org/art/architecture/webb/lahikainen10.html. Accessed 10 Nov. 2025.

MacCarthy, Fiona. “Garden of Earthly Delights.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 26 July 2003, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2003/jul/26/art.architecture.

“Red House’s History: London.” National Trust, www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/london/red-house/the-history-of-red-house. Accessed 10 Nov. 2025.

Webb, Philip (1831 - 1915), English, et al. Red House. 1859. Society of Architectural Historians Architecture Resources Archive (SAHARA). Artstor, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.14923955. Accessed 7 Oct. 2025.

Webb, Philip (1831 - 1915), English, et al. Red House. 1859. Society of Architectural Historians Architecture Resources Archive (SAHARA). Artstor, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.15587784. Accessed 7 Oct. 2025.